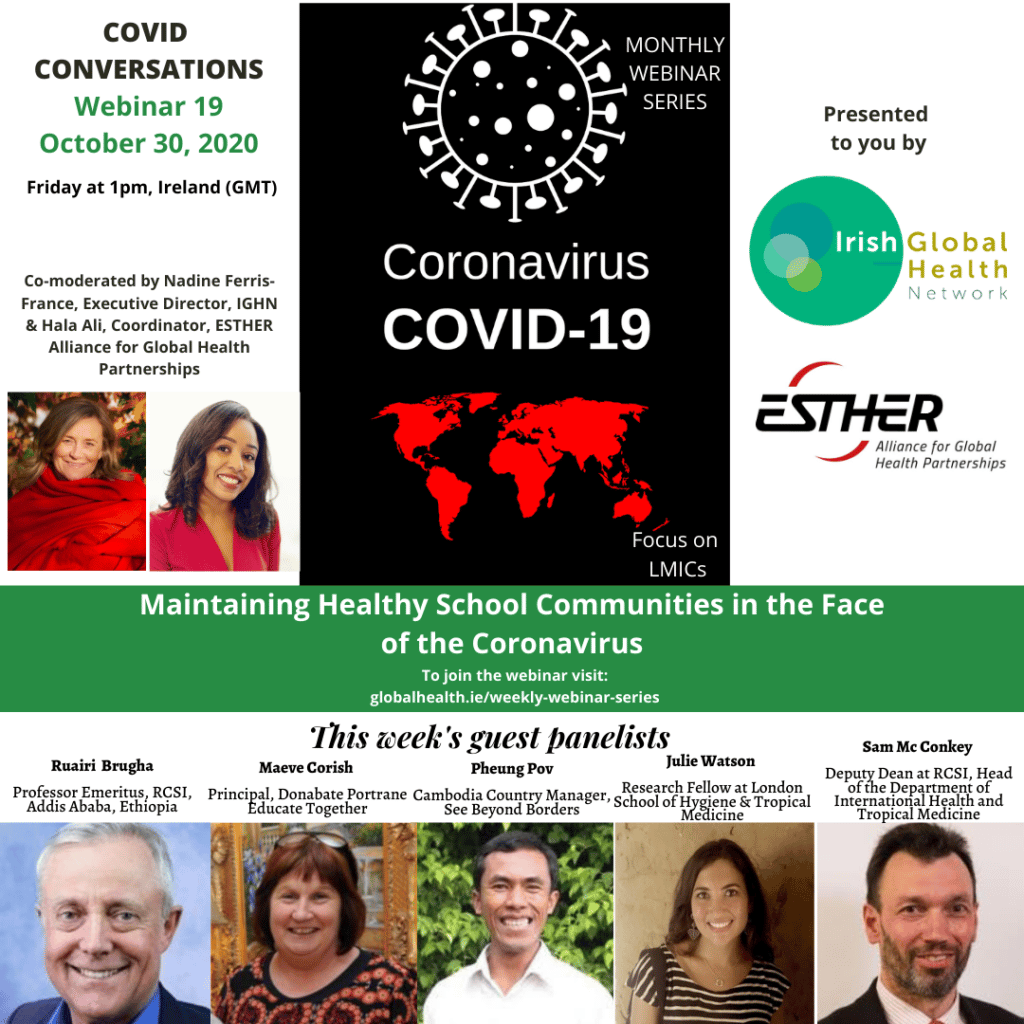

Webinar 19: Maintaining Healthy School Communities in the Face of the Coronavirus

WEBINAR SERIES: WEEK NINETEEN Maintaining Healthy School  Communities in the Face of the Coronavirus

Communities in the Face of the Coronavirus

The full suite of resources shared by speakers is available under each of their individual recordings, along with a summary of the points they made. A full list of additional resources shared by participants and hosts during the webinar can be found at the bottom of the page.

VIEW THE WEBINARYour feedback is important to us so that we can continue to share learnings, insights and practices relevant to those working in the LMIC community. Please take the time to complete our evaluation at the button below so that we can continue to improve the series.

COMPLETE WEBINAR EVALUATIONINTRODUCTION:

According to health officials in Ireland, the risks of coronavirus transmission in schools are acceptable, vis-a-vi the risks and consequences to children of closing schools, with infection rates running at about a third of the rate seen in the overall community. With level 5 restrictions in place for Ireland, it has become a cornerstone of the government’s Plan for Living with Covid-19 to ensure children continue to have the educational and social benefits from attending school, also benefiting parents. However, as community infection rates rise, uncertainty grows about the effectiveness of infection control measures for protecting pupils, staff and the wider school community.

For children in low-resource settings, the consequences of school closures for children’s lives are more serious, given the potential for irreversible or long-term disruption to educational potential; and the risks of increasing child-labour and the particular vulnerabilities of girls, where family poverty can push them into early marriage.

We will hear from representatives of schools in Ireland on the impact of the virus in their schools, and from organisations and individuals in Cambodia and Ethiopia on the consequences of the virus on their community’s education system, health and wellbeing.

We will be asking what we can all do to maintain healthy communities at grassroots level, so that our school communities can continue to educate in environments where the weight of compounding crisis is threatening the preservation of a basic human right for hundreds of thousands of children

A SUMMARY OF POINTS MADE

Sam Mc Conkey: Associate Professor and Head of the Department of International Health and Tropical Medicine at RCSI and a Consultant in General Medicine, Tropical Medicine and Infectious Diseases at Beaumont Hospital Dublin and Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, Drogheda both in Ireland.

Sam speaks about the importance of teachers as essential workers which led to a strong political movement in July and August to get primary, secondary and third-level schools back up and running in September. He describes how systems have changed within primary, secondary and tertiary school institutions and the challenges that were met. Finally, he points to good examples from other countries which can benefit the Ireland educational system

- The chief civil servant secretary general in the department of health moved to the department of education to help with providing educational guidelines to school boards and principals in order to ensure safety of both staff and pupils.

- The challenge has been that our school infrastructure is very diverse. Some pupil to teacher ratio is 15 to 1 whilst others had ratios of 32 to 1. Although the educational system is nationally funded, there is no equality in terms of physical metres squared per student in school or teacher pupil ratios. These measures are important in both educational outcomes as well as being important during a pandemic.

- The third-level educational system is going online or through blended learning. In RCSI, we are testing students as soon as they arrive in Ireland and making sure that they are quarantined in their room for two weeks with bed and board and full support in the two weeks that they arrive. We have also swabbed their noses and tested the sample with PCR. This is to assure the CEOs of the hospitals that our clinical students are not bringing COVID-19 into their clinical attachment

- The modifications seen in secondary schools have seen teachers moving between classrooms, rather than the pupils moving on mass every time the bell rings. So there has been reorganization there. Pupils between the ages of 16-25 are much more of a risk group of socializing together and spreading COVID-19. There is a special unit being set up by the department of health to focus on providing support to teachers, boards and principals to manage those outbreaks quickly.

- The challenge is that there is a delay in testing, follow-up and capacity in Ireland. We have 40 public health doctors in Ireland and we need four times that much and they haven’t been paid properly, they haven’t got proper consultant status and that’s been going on for years, so my view is that we need to build a strong robust public health service in Ireland not just for COVID-19 but for the next 20-30 years to deal with mental health, road accidents, cancer deaths, alcohol, obesity and other global health issues. I hope that our 2 billion increased government investment in the health sector for COVID-19 goes to building a really robust and competent public health service including outbreak detection and management.

- In countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Guernsey, Jersey, Isle of Mann and Greenland there have been quarantine orders and it involves serving people a 14-day notice that they must stay home by law otherwise there will be prosecutions and penalties. However in Ireland we are only doing guidance and recommendations at this point.

Pheung Pov: Pov is Country Manager with SeeBeyondBorders and a pioneering leader and educator. He is a teacher by profession who comes from Siem Reap in northern Cambodia. Pov was the first person to attend high school in his entire district. He joined SeeBeyondBorders in 2013, and has twice visited Ireland as part of the Cambodia Ireland Partnership.

Pov talks about the educational system in Cambodia and how this is affected by COVID-19. He also speaks about the organization SeeBeyondBorders and how they are trying to help both teachers and parents support the education of young people in Cambodia.

- In Vietnam 86 percent of 15 year old children are in grade 10, whilst in Thailand statistics show around 73 percent. However, in Cambodia we have only 11 percent of children in grade 10. In addition, less than 2 percent of their 15-year-olds could read Khmer or can solve simple mathematics equations. 97 percent fail the minimum standard and proficiency. The data shows that on average a pupil will stay in school only for 4.6 years. We see that most students finish primary school however, only 20 percent of students will remain in secondary school. In my case, I was the first and only person to finish grade 12 high school in my entire district.

- COVID-19 has affected the economies very badly because some Cambodians rely very heavily on tourism. It makes up 32 percent of our GDP. This has caused a huge effect on the economy, and so has a knock-on effect on education. The government has tried to support education through distance-learning however, this has been very difficult because some do not have the facility and/or internet. Therefore, people have to come to town to use the internet to support their own education, which has led to a lot of learning loss here in Cambodia.

- The schools in Cambodia have been open from the 7th of September but children are able to learn at school only for 2 or 3 days per week. One day of the lessons will last 4 hours. Therefore, children are able to learn between 10 or 12 hours per week. Class sizes are very big in Cambodia around 45 students per 1 teacher.

- Teachers must wear masks and wash their hands regularly in addition to social distancing measures. Teachers have also been trying to teach online as well but find this very difficult. SeeBeyondBorders has produced some demonstrative videos to help support teachers. We have also produced videos for parents as well. However I feel that the reach is not enough.

Professor Ruairí Brugha, known to us in this webinar series as the webinar anchor. Until the end of 2019, Ruairi was Professor and Head of the Department of Public Health and Epidemiology at RCSI and since then has been contributing to debates in Ireland on COVID-19 control since March 2020. In August he moved to Ethiopia from where he continues to contribute to global surgery and health systems research.

Ruairi talks about the educational situation in Ethiopia and measures we can learn from Ethiopia. He also describes and shares some guidelines to combat the social and psychological effects COVID-19 has on children and their knock-on effects on parents during lockdown.

- Ethiopia is 20 times bigger than Ireland and has around 46,000 teachers who are going to be trained to teach and take up the role of being responsible for COVID-19 control in schools. Stress levels directly related to COVID-19 is less in Ethiopia. However, it’s the indirect effects of the control measures that really cause more damage than the impact of COVID-19 itself.

- Firstly it’s a matter of balancing risk, Ethiopia as well as other sub-saharan African countries may look like they are having a milder first wave so there is an assumption for strong case for schools to be open. This is particularly strengthened by the risks in Africa for children being out of school for long periods. The education regression that happens is much more difficult to catch up on later. Children may also be diverted into income generated jobs or into child labour. There may be a risk of domestic violence and particular risks to girls around forced marriage and sexual exploitation. However, if community transmission gets much worse, then there may be a case for closing for longer periods and mass testing.

- For those who are familiar with Ethiopia, they will be aware of the health extension workers. Health extension workers are former community health workers whose usual responsibilities lie within the community. Now they are being given the responsibility in COVID-19, where they will actually come into the schools and will act as a communication channel between the health services and the schools. Their role is to be there to educate students and teachers on how to protect themselves and ensure the preventive measures are in place. They will also work with volunteer student teams and student health clubs. Maybe this is one that we should be looking at in Ireland, taking sixth grade students and giving them a particular role in monitoring and encouraging compliance with preventative measures. This allows pupils to perform peer education and to do outreach activities within the community. So in Ethiopia’s strategy there is a very strong link between the community and the schools.

- The difficult thing is also about managing the symptomatic child. To make decisions around children who have had contacts at home. The three resources which are shared (which you can find below) one of which is a guideline from the HSE gives advice on a symptomatic child. The other is a clinical decision tree which is used to help guide the school health staff in how to make those decisions and how to give advice to people. People need those kinds of tools to manage those difficult areas.

Maeve Corish: Maeve is an Irish primary school teacher working in primary education for over 38 years. She has a Masters in Human Rights and Citizenship and she is passionate about equality, justice issues and the nurturing of inclusive schools. She has spent the last 18 years as the principal teacher of Donabate/Portrane Educate Together National School (DPETNS). DPETNS are proud members of the Cambodia/Ireland Changemaker Network.

Maeve speaks about her own personal experiences of being a teacher in the face of COVID-19. She talks about the challenges of implementing COVID-19 social distancing measures in schools and what she would like to see in future.

- It is so important that we keep our schools open as much as we can. We have had two phases of the impact of COVID in our schools. The first was the school closure and it happened very abruptly and we were plunged into remote learning which we were not prepared for. Everyone was on a very steep learning curve and everybody struggled. The second phase was the reopening of schools this turned educators into health experts. Teachers were moving into a field in which they had no experience or training in.

- The biggest impact COVID-19 is having is with the increased anxiety levels and the awful feeling of uncertainty. I personally believe that the best we can do for kids is to give them their routine, sense of normality, sense of connection and socalisation that they get from school. Because of COVID children are behind academically due to missing a lot of formal schooling particularly in disadvantaged areas in Ireland or in certain LMICs such as Cambodia or Ethiopia. Therefore it is important for us to try our hardest to keep schools open.

- Social distancing in schools is a big challenge. Most of our classrooms have 30+ children in them with a teacher and probably an SNA (Special needs assistant). We can seat our children one meter apart but they have to move around the classroom and they have to be children. So it’s getting the balance right with social distancing. Ventilation is also another big issue to try and make sure that there’s a flow of air through the classrooms. A couple of other challenges include staff being absent, managing sick children in school and communication.

- In the future, I would like to see better contact tracing. In communities where levels of COVID-19 are very high I’d like to see schools closing or even schools operating on smaller numbers so that we can implement proper social distancing measures. There should also be the idea of ‘circuit breaker’ where schools are open for six weeks and then closing for two weeks to try and stop the spread of disease. Wellbeing is top of the agenda for all of us at the moment. One of the best ways to increase wellbeing is to get people to focus outside of themselves and look at ways other countries are dealing with COVID-19. This takes you out of your own negativity and looking at the world in a broader way.

Julie Watson: Research Fellow at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Her research focuses on the epidemiology of disease related to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and the design and evaluation of WASH interventions to control these diseases.

Julie speaks about the three key actions to reduce person-to-person transmission which includes promoting physical distancing, promoting good respiratory hygiene practices and finally promoting good hand hygiene practices in schools.

- One of the ways to promote physical distancing in schools is to use visual cues in the environment, so for example placing marks on the floors to cue children to stand the correct distance apart. Another method is demarcation of playgrounds into zones, which can reduce mixing of children or just reducing the density of the building by introducing one-way systems to move through the building. Finally, eliminating school gatherings, such as cancelling school assemblies, sports events and restricting gathering spaces will also promote physical distancing

- For promotion of respiratory hygiene, this should be incorporated into the curriculum alongside broader hygiene promotion. It should be noted that children up to the age of five is advised that they should never really wear masks. However, teachers in schools should have some agency over deciding where masks are or are not appropriate. Ventilation is really important and should be maximized when the climate allows.

- In terms of promoting good hand hygiene behaviours, school must create an enabling environment so at a very minimum there needs to be hand-washing facilities with soap and water available at all times. This is the JMP (joint-monitoring projects) requirement for basic hygiene in schools. These facilities should be accessible to all users. Hand hygiene promotions should be included as part of the curriculum but when promoting this there must be a consideration of age, gender, ethnicity and disability as well. Especially amongst younger children, it is important to create a schedule for children to hand wash as part of their routine and habit.

Further Resources:

- HIQA HTA Review COVID in school children 4-9-20: https://globalhealth.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/HIQA-HTA-Review-COVID-in-school-children-4-9-20.pdf

- School-based Algorithm: https://globalhealth.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/School-based-Algorithm.pdf

- Isolation quick guide V2 16092

- Final Draft_School Preparedness and Response Guideline_V1: https://globalhealth.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Final-Draft_School-Preparedness-and-Response-Guideline_V1.docx

- https://www.seebeyondborders.org/

- Using Environmental Nudges to improve Handwashing with Soap among School Children – A Resource Guide for rapidly deployable Interventions for use as an interim Measure during School Reopenings

CATEGORIES

- Restore Humanity Campaign

- Equity in Action Blog

- Training Programmes

- Sponsorship

- Vaccine Equity

- Get Global – Global Health Talks

- Student Outreach Team

- Get Global Young Professionals Talk Global Health

- Global Health Matters – Live Event Series

- Global Health Matters – IGHN Live Event Series

- An initiative of Irish Global Health Network

- ESTHER Ireland and ESTHER Alliance for Global Health Partnerships

- Global Health Matters – Webinar Series

- ESTHER

- IGHN Conferences

- Global Health Conference 2020

- Women in Global Health – Ireland Chapter

- ESTHER Partnerships

- Weekly Webinar Series

- 4th Global Forum on HRH

- Access to Medicines

- Archive Page Weekly COVID Webinars

- Clean Cooking 2019

- Climate Change and Health Conference 2017

- Conference Abstracts

- Conference Materials

- Covid FAQ

- COVID Funding Opportunities

- COVID-19

- COVID-19: Gender Resources

- Dashboard and online resources

- Education

- ESTHER Alliance

- Events

- Events & News

- Funding covid

- Global Health Exchange 2018

- Global Health Exchange 2019

- Global Health symposium 2019

- Health Workforce/HRH

- Homepage Featured

- Homepage recent posts

- IFGH 2011-2012 Conference and Events

- IFGH 2014 Conference

- IFGH Multimedia

- Irish AIDS Day 2017

- Irish News and Feeds

- Key Correspondent Articles

- Key Correspondent News

- Maternal Health

- Multimedia

- News

- News & Events

- Newsletter

- Opportunity

- Our LMIC's Resources for COVID19

- Partner Country News and Feeds

- Past Events

- Policy

- Presentations

- Recurring events

- Reports & Publications

- Research

- Resources

- Student Outreach Group

- Students Corner

- TEDTalks

- TRAINING COURSES FOR HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Events

RECENT POSTS

Impact testimonies- Lombani

Impact Testimony – Shadrick

Power, Inequality, Decolonisation – and Living My Recovery By Bronwyn April

Global Health Without Borders: Reflections on the Power of Diverse Voices

IGHNxEU – Empowering Women for a Healthier Europe