‘From refugee to stateless, you are still not illegal’

By Key Correspondent for the Irish Global Health Network, Riya Tripathi

By Key Correspondent for the Irish Global Health Network, Riya Tripathi

Imagine being born in a country that you call home and not being called a legal citizen of that country. Being legally stateless. The very first thoughts you might have of the word ‘stateless’ are of a person who neither belongs to a country nor is accepted legally by any other country. Patricia Erasmus, a judicial researcher from the Supreme Court of Ireland, presented several challenges regarding statelessness in Africa at this year’s Global Health Exchange held at Dublin City University. Her research work shed light on how statelessness must be considered a health and a feminist issue.

In layman’s terms, a stateless person is someone who cannot avail of services by the government of a country and has no nationality. Ms. Erasmus’s research focused mainly on statelessness caused by inadequate access to birth registration. Her work projected a clear picture of how stateless people from South Africa are marginalized from accessing human rights, health, and other socio-economic rights. The plight of stateless people does not just end there. If we look at the bigger picture, it has become a health issue: access to date of birth registration improves healthcare access in general. Since birth registration is something that is mostly initiated by mothers (in this case South Africa) it is fair to say that it falls within the sphere of a feminist issue as well.

While working on the ground with migrants, Ms. Erasmus noted that many are treated more or less like ‘ghosts’. They simply cannot do anything – they cannot migrate legally, cannot register their children’s birth, cannot get married, and cannot benefit from social welfare services. With no birth certificate and no proof of any kind of documentation, they are living in limbo.

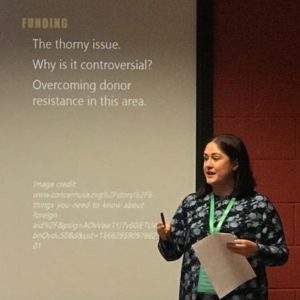

Ms. Erasmus’s research work revealed how African children are recognized to be double-disadvantaged by their own states. The research also focused on different approaches such as the grassroots education program in Africa, and development of education or human rights. Ms. Erasmus’s presentation made it clear that so much brilliant work is being done in terms of grassroots education, citizenship rights and African initiatives. Nonetheless there is space for more to be done. However, the question is who will provide the funding backbone for this work?

The thorny issue with funding for programmes supporting stateless people is the controversy. It is very difficult as an external donor to implement funding strategies which advocate to a country who they can or cannot give citizenship to. Surprisingly, the research indicates that birth registration is one way citizenship rights in Africa can be increased through the back door.

The synergy between healthcare rights and birth registration is clear. If we can increase access to birth registration it will help an immediate rise in healthcare rights realization, and will have an ancillary effect of eradicating statelessness to a larger extent. It is necessary to say that statelessness is caused by many factors. For example, in the case of India, the government published a list of people stripping them of their citizenship. To these individuals, birth registration will be of no avail but unlike the African example, they are at least still in possession of some sort of proof of identity.

The first steps to making change have been taken and, the universal birth registration campaign has started progressing in Africa. This campaign has the potential to break the never-ending cycle of poverty caused by statelessness, leading to a slightly brighter future. However, even this campaign will not be successful in the long run if states do not participate. Legal reforms at either regional or national level need to be made in favor of stateless people, especially women who experience added vulnerabilities.

Ms. Erasmus noted that, “when you have a hammer every problem looks like a nail, “concluding her presentation. So trying to force healthcare rights, or pushing governments to adopt sub-strategies which would promote funding or introduce legal reforms just for money, is the last way to resolve the issue. Expansion of rights through the back door will only give a quick-fix and would be unsustainable. Instead, by working hand in hand to develop socio-economic rights, healthcare rights and others, there is hope that we can curb this issue and support stateless people to achieve their fundamental rights as human beings.

27 September 2019

CATEGORIES

- Restore Humanity Campaign

- Equity in Action Blog

- Training Programmes

- Sponsorship

- Vaccine Equity

- Get Global – Global Health Talks

- Student Outreach Team

- Get Global Young Professionals Talk Global Health

- Global Health Matters – Live Event Series

- Global Health Matters – IGHN Live Event Series

- An initiative of Irish Global Health Network

- ESTHER Ireland and ESTHER Alliance for Global Health Partnerships

- Global Health Matters – Webinar Series

- ESTHER

- IGHN Conferences

- Global Health Conference 2020

- Women in Global Health – Ireland Chapter

- ESTHER Partnerships

- Weekly Webinar Series

- 4th Global Forum on HRH

- Access to Medicines

- Archive Page Weekly COVID Webinars

- Clean Cooking 2019

- Climate Change and Health Conference 2017

- Conference Abstracts

- Conference Materials

- Covid FAQ

- COVID Funding Opportunities

- COVID-19

- COVID-19: Gender Resources

- Dashboard and online resources

- Education

- ESTHER Alliance

- Events

- Events & News

- Funding covid

- Global Health Exchange 2018

- Global Health Exchange 2019

- Global Health symposium 2019

- Health Workforce/HRH

- Homepage Featured

- Homepage recent posts

- IFGH 2011-2012 Conference and Events

- IFGH 2014 Conference

- IFGH Multimedia

- Irish AIDS Day 2017

- Irish News and Feeds

- Key Correspondent Articles

- Key Correspondent News

- Maternal Health

- Multimedia

- News

- News & Events

- Newsletter

- Opportunity

- Our LMIC's Resources for COVID19

- Partner Country News and Feeds

- Past Events

- Policy

- Presentations

- Recurring events

- Reports & Publications

- Research

- Resources

- Student Outreach Group

- Students Corner

- TEDTalks

- TRAINING COURSES FOR HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Events

RECENT POSTS

Impact testimonies- Lombani

Impact Testimony – Shadrick

Power, Inequality, Decolonisation – and Living My Recovery By Bronwyn April

Global Health Without Borders: Reflections on the Power of Diverse Voices

IGHNxEU – Empowering Women for a Healthier Europe

By Key Correspondent for the Irish Global Health Network, Riya Tripathi

By Key Correspondent for the Irish Global Health Network, Riya Tripathi